Soundscapes and Anachronisms in Music for Laptop Ensemble

The development of the laptop ensemble in the 21st century has produced new frameworks for exploring connections between technology, nature and history. What changes when environmental sounds and recordings of earlier music are taken outside of the fixed-media domain and realized through structured improvisations based on listening, gestural control and interactions with malleable digital instruments? The prevalence of the laptop ensemble or orchestra as a workshop or ensemble within post-secondary learning environments has created a platform for exploring novel approaches to music pedagogy in which digital lutherie allows users to move freely through a cultural past and into the future. These classroom or rehearsal settings are also well suited for exploring laptop improvisation in relation to research-creation. With the use of sampling and synthesis to recall and emulate familiar sounds and musical works, interactions with and through laptop instruments can act as a tool for knowledge dissemination. The flexibility of the instrument and the ensemble also creates opportunities for building connections between technologies (e.g., coding), compositional structures and the natural sound environment. In a discussion of music for laptop ensemble that has explored these relationships, we focus on works that were played and workshopped during the author’s time spent directing the Cincinnati Integrated Laptop Orchestra Project (CiCLOP), and examine the intentions and results of the ongoing research-creation project Code, Sound and Power.

Networked Nature Music

In fixed-media electroacoustic compositions that rely on sounds from the natural environment, the composed work and the act of listening during a so-called “schizophonic” presentation with loudspeakers or headphones combine to form a sense of liveness in music. Whether it be in soundscape composition or acousmatic sound work that relies on a greater amount of source transformation through processing, the listener makes associations and assembles meaning through the connection of sound symbols that help realize the world assembled within the audio. In live electronic music, the relationship between listening and creation is augmented as performers negotiate between intended and realized sound output. The manners in which laptop music references nature can range from the construction of soundscapes through group improvisation with field recordings to the use of computer-generated, synthesized sounds that suggest, imitate or model the environmental sounds. There are also works that establish programmatic connections to aural and visual aspects of the natural world. In the process of building and workshopping digital instruments for connecting pitch/timbre and duration structures to environmental noises that inspire a sound work, the strategy in the author’s own creative work and research for laptop ensemble has been to use tools that are equally focused on gestural control and code sharing among the networked ensemble.

(Re)Building Soundscapes Through Performance

Mara Helmuth’s recent works for laptop ensemble have been influenced by research activities that have allowed the composer to interact with unique natural sonic environments through travel. In pieces such as from Uganda (2014) and from Australia (2016), players collaborate to produce a unified sonic topography using excerpts from field recordings that are accessed through a Max/MSP interface. There are two soundscapes simultaneously projected during performances of these works. The real setting, as experienced and recorded during the composer’s travel, is established using the sound files as a form of documentation. An additional virtual soundscape is produced by the ensemble live during the performance. The latter is created and shaped using effects processing and is composed via selective listening choices that are often influenced by spatial aspects and communication within the group through networked text cues and sonic gestures. This second space becomes more readily accessible as an artistic field of sonic exploration through the abandonment of the ensemble or orchestra conductor role that was often used in earlier laptop ensemble models. The design of Helmuth’s laptop ensemble pieces (including the system and the structure of the improvisation) shares similarities with other improvised computer music practices that seek to access new spaces by emphasizing collaboration over performance models borrowed from earlier concert music genres. In reference to his work with interactive computer programmes such as Voyager (1987), George E. Lewis states that system design and interactions contribute to “non-hierarchical, collaborative, and conversational social spaces that were seen as manifesting resistance to institutional hegemonies” (Lewis 2018, 127).

In from Uganda (Video 1) and from Australia, the effects processing modules in each performer’s instrument rely on reverb, comb filters and Helmuth’s own granular synthesis instruments made for the RTcmix language. In terms of potential for simple code-sharing among the networked ensemble, performers are able to modify the RTcmix scripts for synthesis or processing that are stored in the same directory as the Max/MSP patch and then call them up within the UI, or even send them through UDP messaging. The use of effects processing is not limited to transformation or abstraction of field recordings. It is also exploited to render individual sounds or textures with a degree of exaggeration or ambiguity. This aspect contributes to the creation of “fuzzy boundaries” between the setting produced through literal documentation of travel and the one simulated that can only be represented through performance. For example, the ambient stuttering of trucks from field recordings can be made a focal point in laptop ensemble performances through the use of sound file granulation that syncs duration and rate parameters with engine noises (Audio 1). Latent pitched sounds can be magnified through the use of comb filters with peaks that share a degree of harmonicity with sound sources such as bird calls. In establishing these connections between the sound recordings and effects processing, user interface objects such as sliders with unspecified ranges challenge the performer to adjust based on what they hear coming out of the patch (Fig. 1). This aspect of the piece allows the players to explore the relationship between effects parameters and characteristics of the source material during the performance of the work.

Balancing the real and the imaginary is an established practice employed in fixed soundscape works. Hildegard Westerkamp writes of soundscape listening and composing as “located in the same place as creativity itself: where reality and imagination are in continuous conversation with each other in order to reach beneath the surface of life experience” (Westerkamp 1999). The manner in which laptop orchestra music can simultaneously project multiple spaces has also been explored in pieces such as Scott Smallwood’s On the Floor (2006), in which there is an audible separation between diegetic sounds that resemble a casino environment and non-diegetic soundtrack music. Affecting changes in effects processing by manipulating a Max/MSP patch is only one of the ways that players create a second space in that work (Smallwood et al., 11).

While some performances of Helmuth’s laptop music relied solely on the Max/MSP patch as the main performance instrument, these pieces have been workshopped and performed using additional mobile devices that connect to the patches through Cycling 74’s Mira application. One of the motivations for using mobile devices is that their own spatial orientation becomes an additional parameter in a performance. An extra layer in the sense of space produced by this mobile version of from Uganda and from Australia is the mapping of pitch, roll and yaw information from the gyroscope within each device to control the parameters such as the room size of a reverb object in Max/MSP.

Earlier laptop orchestra workshops emerging from academic settings tended to rely on the existing orchestra metaphor, localizing each player’s sound contributions with the use of hemispherical speaker arrays. While hemisphere speakers were used in rehearsal and workshop settings due to their relative portability, performances of Helmuth’s laptop music by the Cincinnati Integrated Composers Laptop Orchestra Project (CiCLOP) relied on octophonic setups with which the player’s sound output can be mixed across the loudspeaker array. This approach was used to promote the idea of the laptop ensemble as a meta-instrument that plays soundscapes. The lack of fixed seating for performers, gestural control of reverb and the use of a multi-channel system to distribute the group output presents a framework in which the laptop ensemble can use the combination of performance and listening to gain special access to new sound spaces.

Between Music and Nature

While Helmuth’s approach uses recorded sounds as the foundation for each piece, some recent laptop music relies on synthesis and processing of electronic sources to create computer-generated emulations of environmental sounds. John Gibson’s Wind Farm (2009) was workshopped by CiCLOP and included as material for the 2016 Laptop Performance course (COMP 6083) at the University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music. The simplicity of the gestural controls used to play Wind Farm contributed to the success of the piece as material for a laptop performance class. The use of a trackpad to flick, drag and swipe meant that players felt less challenged to perform virtuosically and could instead divert their efforts to creating sounds that were compatible with others in the group, as well as with the extra-musical aspects of the piece. Wind Farm builds upon a tradition of fixed electroacoustic works — notably Jean-Claude Risset’s Sud (1985) and Barry Truax’s Riverrun (1986) — in which the use of sound synthesis makes references to nature. While no genuine soundscape is produced by the laptop ensemble for Wind Farm, as is the case for Mara Helmuth’s laptop ensemble works describes above, it also relies on listening and gestural control, led by networked messages from a conductor. Instead of playing on the ambiguity between real and imaginary, Gibson’s piece conveys the real through the imaginary.

Wind Farm relies on synthesis-based objects such as a physical model of a Helmholtz resonator based on the BlowBottle class from the Synthesis Toolkit (Cook and Scavone 1994), and on processing effects such as spectral delays to create sounds that are simultaneously referential of nature and easy to manipulate, because of the use of pitch classes encountered in non-electronic music genres (employed via frequency-to-MIDI-note conversion within the individual player patches) and indications using note letter names for the conductor patch (Fig. 2). The use of a melodic contour that develops across an arch-like form and the voicing of harmonies using largely consonant intervals in the outer voices give the piece a proximity to structural elements conventionally used in the composition of Western art music. The pitches are distributed to the players through cues within a conductor patch, meaning that while the piece is framed around a composed form and harmonic progression, the spontaneous physical gestures of individual players are what develop the motivic content and establish the connection to the extra-musical wind energy references. Within the Laptop Performance course, the piece was also considered from a research-creation point of view. While the use of musical instruments to imitate nature sounds is a well-established practice in art music using notation and sound recordings — Ottorino Respighi’s Pines of Rome (1924) comes to mind — and the use of synthesis as a means of transcription exists in fixed-media electroacoustic music, the design of instruments that allow for improvisation with synthesized transcriptions of real-world sounds represented a “creation-as-research” approach that allowed for the uncovering of connections between technology, nature and the student’s individual relationship with pitch, harmony, rhythm, etc. Students were subsequently asked to apply this model to design their own laptop ensemble pieces for course workshop sessions.

The author’s Code, Sound and Power (CSP) project was initially funded through Mitacs as a Research Training Award for teaching coding literacy and musical concepts in tandem using laptop improvisation. The initial state of the project included facilitator-led training and improvisation sessions in which group members used a combination of Max/MSP, Cycling 74’s Miraweb platform and the RTcmix language to make references to the timbres, rhythms and trajectories of environmental sounds. Compositionally, the use of structured improvisations that function as responses to nature themes was meant to counter the feeling of isolation that can occur in the context of remote performance. It helps establish a connection to the outside world from within the virtual environment (the web browser and Max/MSP via UDP messaging). While some laptop ensemble music focuses on the spatial disposition of the performer and output routing that emphasizes individual location (e.g., hemisphere speakers) 1[1. See, for example, Joo Won Park’s Singaporean Crosswalk (2016) or Ge Wang’s Clix (2006).], in the CSP project, individual efforts are combined in a stereo mix as a way of deemphasizing individual virtuosity so that code contributions by beginners and advanced users are given equal space within the improvisation. This project builds on previous work that explored the potential for the laptop ensemble or orchestra as a tool for novel approaches to music pedagogy in which making music using code motivates players to learn through experimentation (Wang et al. 2008, 32).

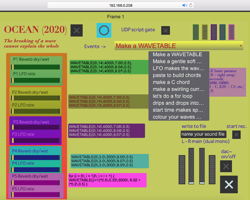

After a virtual private network (VPN) has been created, session participants use their browser to enter a Miraweb page that projects the interface for a Max/MSP hub patch containing audio processing and mechanisms for sorting the code sent from each participant as a unique, player-specific UDP message. Each training and improvisation session begins by working through the author’s laptop ensemble work Ocean (2020). This particular improvisation is used as an original sound work and a way of becoming familiar with the tools for sending, viewing and evaluating code. The Miraweb interface also includes tools for processing the live-coded sound output (Fig. 3). The use of additional effects processing, delays and looping devices could be viewed as a departure from the popular live coding practice of building algorithmic music entirely with a text-based environment within a blank project screen, but the use of delay lines and looping has proven useful. This project is about education through creation and is meant to demonstrate the expressive power of coding for beginners and experts alike. The focus is not on developing a high level of technical mastery with the RTcmix language, but rather to understand how beginner and intermediate devices like variables, loops and conditional statements can relate to particular sonic results that are idiomatic of code-as-instrument. Accompanying coded music efforts with effects processing and live sampling helps create a sense of continuity as improvisations gradually unfold (Fig. 4).

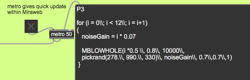

In Ocean, along with the other pieces produced for the project, a session facilitator guides the group through a set of cues that instruct the players to initiate coding tasks that involve synthesis and musical concepts, and use them to transcribe nature sounds. From a live coding and performance perspective, the key difference from Gibson’s work is that CSP relies on a code-as-instrument approach (with some modifications made by adjusting sliders in the Max/MSP interface), whereas Wind Farm is performed using a trackpad and individual keystrokes. For example, the session participants learn to use low-frequency oscillators to reference the motion of waves in the sea, and a for loop with randomization to create asynchronous particles that mimic rain sounds.

Also created within CSP, the author’s piece Wind relies on two RTcmix instruments: MBLOWHOLE, a clarinet physical model, and PINK, a pink noise generator. As with John Gibson’s Wind Farm, the laptop instrument (in this case the use of code as an assemblage of objects and commands) is used as an intermediary between defined pitch structures typical of Western instrumental music with its discrete divisions of the octave (whether equal temperament or linear octave notation) and spectrally complex synthesized nature sounds. The clarinet model can be “played” as a software implementation of an acoustic instrument, but its “noise gain” and “breath pressure table” functions can be used to create a variety of wind-like sounds. Players are encouraged to play on this dual identity of emulation of nature and clarinet by using the model to produce sounds that oscillate between pitched motives and melodies to breathy sounds and broad noisy gusts of synthesized wind (Fig. 5). In addition to the RTcmix instruments, a bank of resonant bandpass filters can be controlled using a Max/MSP user interface slider to transform the collective wind field.

Laptop Instruments and Musical Anachronisms

In addition to music that was based on nature sounds, CiCLOP was also interested in playing laptop ensemble music that relied on digital instrument design and performance as the basis for pieces concerned with intertextual exploration and the integration of sound and coding objects from various genres and historical eras. Since the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music served as a hub for rehearsals and performances, the laptop ensemble was a productive vehicle for critical reflection on each player’s positionality with regards to the canonical “Western art music” that was so prevalent in that institution. The inherent malleability of digital instruments allowed the ensemble to create a variety of structured improvisations based on different genres and musical artifacts. A principal concern was how to perform with such resources in a way that disseminates new perspectives and interpretations, or previously unheard aspects of the suggested sound content: not using the laptop as a reduction of a concert instrument but rather as a way of unearthing something new about the music.

Accessing Music with Sampling and Sensors (Old Dogs, New Tricks)

The author’s all the moon long… (2015) is based on sleep in a literal, scientific sense and explores the suggestion of sleep through references to programmatic music. Aspects of tonal music are heard, but motives are reproduced and superimposed upon fragments of existing music using a combination of sampling and gestural sensor input. The manipulation of audio files using a trackpad, QWERTY keyboard and gestural control via a Nintendo Wiimote 2[2. Technically called a Wii Remote, colloquially known as a Wiimote.] and the Sudden Motion Sensor (SMS) found in MacBooks 3[3. The Sudden Motion Sensor was a component of Apple MacBooks. It was originally designed to detect motion and protect data, but its components can be mapped to pitch, roll and yaw data so the user can control musical parameters in an environment such as Max/MSP.] builds on the notion of sampling as an act of generic and historical disruption. For popular music scholars like Vanessa Chang, “sampling maintains an ethics [sic] of inclusion that is social as well as musical, creating a tradition that involves the past without submitting to its structures and limitations” (Chang 2009, 156). While the kind of sampling that Chang discusses takes place in the studio, another layer of disruption is added by the use of a laptop instrument that requires physical gestures that are not typically associated with the original composition. In the author’s all the moon long… (2015), the tilting of the laptop or the Wiimote to affect parameters such as the playback rate and gain of sound offer a new approach for playing or playing with samples such as a piano recording of Brahms’ Wiegenlied [Lullaby], and the use of gestures to control granularization of the sound file adds the ability to zoom into particular harmonies and articulations in a way that would not be available in a piano realization of the piece (Video 2). The performance using a newly constructed digital instrument may not sync with the perception of this music as an artifact of European Classical music, but the laptop ensemble setup helps disseminate new ideas about the state of such a piece in contemporary culture.

Video 2. Rehearsal of the author’s all the moon long… (2015) on 14 June 2016 for its performance in NYCEMF. Vimeo video “Michael Lukaszuk — all the moon long…” (5:55) posted by “Michael Lukaszuk” in 2016.

The ability to dive into a sound recording through live manipulation of looping and granular sampling also emphasizes the importance of listening as part of the realization of these anachronistic laptop ensemble works. While larger sound fragments that amount to quotations may steer the audience towards narrative listening, the intervention of software and controllers shift the experience towards meditative listening. The ability to interact with Classical music repertoire in a way that is dissociated from form or linear phrase structures allows opportunities for hearing specific qualities in the referenced piece or recording. For example, in all the moon long… (Fig. 6, Video 2) the performer can use the SMS sensor to control the buffer offset of a sound file to highlight the syncopation, or pair the Wiimote so that it maps filter parameters in addition to granularization that can emphasize or even shift the strongly emphasized E-flat pedal tone in the sampled Wiegenlied recording.

Figure 5. In Wind, Michael Lukaszuk encourages players to create a “fuzzy boundary” between the MBLOWHOLE instrument as a clarinet model of a wind-sound generator by at times emphasizing breath and noise functions over pitch and frequency control.Figure 5. In Wind, Michael Lukaszuk encourages players to create a “fuzzy boundary” between the MBLOWHOLE instrument as a clarinet model of a wind-sound generator by at times emphasizing breath and noise functions over pitch and frequency control.

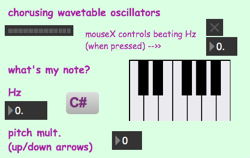

Inspired by Heitor Villa Lobos’ fusion of Brazilian and baroque music in Bachianas Brasileiras, the author’s Bachiana (2017) considered the fusion of laptop improvisation and the music of J.S. Bach using both the individual laptop instruments and the combined output of the ensemble. In this piece, the laptop instrument is used as a tool for reflection and superposition on the notion of harmonicity and harmony in Bach’s music. Bachiana explores the potential for laptop ensemble music as a vehicle for research-creation (or research-as-creation). While group laptop improvisation can be fulfilling as a social form of music creation, it can also be used for “epistemological intervention into the ‘regime of truth’ of the university” (Foucault cited in Chapman and Sawchuck 2012, 6). In Bachiana, the use of QWERTY keyboard input and trackpad control within a Max/MSP interface allows users to weave in and out of Bach’s tonality, while at the same time projecting new harmonic idioms from interactions with sampled recordings of The Goldberg Variations. For example, in the module seen in Figure 7, players use keyboard input to play wavetable oscillators in a way that imitates fragments of pieces by Bach that are being sampled by other performers in the ensemble. They can use the trackpad to adjust the level of harmonicity or inharmonicity by either detuning the frequency or distorting the waveform using a chorus effect. Subsequent versions of the piece allow for effects processing of the patch output using RTcmix scripting, borrowing the approach to blending code sharing and gestural performance from the CSP project.

Conclusion

While the exploration of interactions between technology, nature and artifacts from earlier eras in music history is not a new phenomenon, the laptop ensemble adds new frameworks for exploring how listening, spatialization and the intertextual relationships can emerge from electroacoustic composition and improvisation. The use of both recordings and synthesis shows how digital instrument design can act as a bridge between structural musical materials that are familiar to the composer and the characteristics of natural or acoustic sound sources. Such connections are valuable when exploring the laptop ensemble as a tool for novel approaches to music pedagogy in that they can critically situate works that are perceived as canonical in contemporary music performance.

December 2021, April 2022

Bibliography

Chang, Vanessa. “Records That Play: The present past in sampling practice.” Popular Music 28/2 (May 2009) pp. 143–159. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143009001755

Chapman, Owen B. and Kim Sawchuck. “Research-Creation: Intervention, analysis and ‘family resemblances’.” Canadian Journal of Communication 37/1 (April 2012) “Media Arts Revisited,” pp. 5–26. http://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2012v37n1a2489

Cook, Perry and Gary Scavone. “The Synthesis Toolkit in C++ (STK).” http://ccrma.stanford.edu/software/stk

Gibson, John. Wind Farm (2009), for laptop ensemble. Max/MSP patches. http://johgibso.pages.iu.edu/pieces/windfarm.html [Accessed 16 April 2022]

Lewis, George E. “Why Do We Want Our Computers to Improvise?” In The Oxford Handbook of Algorithmic Music. Edited by Alex McLean and Roger T. Dean. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190226992.013.29

Smallwood, Scott, Dan Trueman, Perry R. Cook and Ge Wang. “Composing for Laptop Orchestra.” Computer Music Journal 32/1 (Spring 2008) “Pattern Discovery and the Laptop Orchestra,” pp. 9–25. http://doi.org/10.1162/comj.2008.32.1.9

Westerkamp, Hildegard. “Soundscape Composition: Linking Inner and Outer Worlds.” Soundscape Before 2000 (Amsterdam, 19–26 November 1999). Posted on the author’s website 19 November 1999. Available at http://www.hildegardwesterkamp.ca/writings/writingsby/?post_id=19 [Accessed 16 April 2022]

Wang, Ge, Dan Trueman, Scott Smallwood and Perry R. Cook. “The Laptop Orchestra as Classroom.” Computer Music Journal 32/1 (Spring 2008) “Pattern Discovery and the Laptop Orchestra,” pp. 26–37. http://doi.org/10.1162/comj.2008.32.1.26

Social top