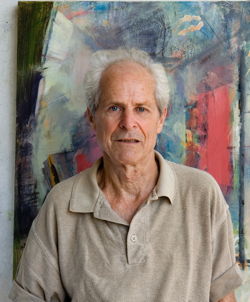

Interview with Tony Martin, Liquid Light Artist and Painter

A Visual language of enormous and tiny, brilliant and slimy, dark and fuzzy

The following interview was videotaped in Tony Martin’s home in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York City on 21 March 2008. The transcription of the audio was crafted by the author, with Martin’s assistance, into a first-person narrative for its initial publication in EMF. Further refinements to the text were integrated in 2021–22 (clarifications of anecdotes and descriptions, names, etc., and slight improvements for the sake of readability) in view of its subsequent publication in eContact! 21.1 (May 2022).

This 2008 interview, recorded by musician Robert Gluck at the Brooklyn studio of the unique artist-inventor Tony Martin, covers aspects of Martin’s formative years, his early training as a musician and his subsequent embrace of visual art as an inquisitive and unbounded vehicle for ground-breaking works employing pure light, painting techniques and use of technology from the 1960s onward. Specific points of interest include Martin’s San Francisco influences and his work with musicians and new music composers, not to mention his involvement with the San Francisco Tape Music Center and the Electric Circus in New York City, and his collaborative work with other notable artists. Martin comments on his æsthetic directions and decisions, and offers a rare look at how he integrated repurposed prisms and multi-material slides as essential components of his artistic palette.

http://www.tonymartinartist.net

Childhood in New Jersey

I grew up in a little town in Roosevelt, New Jersey. It was a very unusual town, somewhat socialist. It was begun by mostly Eastern European Jewish immigrants and clothing workers and some artists. Ben Shahn lived there and painted the mural in the school that I walked into every day. Ben’s mural, which included a depiction of Albert Einstein, was very important to me. 1[1. As Ben Shahn’s Roosevelt / Jersey Homesteads Mural dramatizes, theirs was also the story of escape from dark tenements and sweatshops in the city to simple but light-filled homes and cooperative garment factory, store and farm in the country.] The houses were designed by noted architect Louis Kahn and an assistant. He was loathed by the residents. They called them “chicken coops” because they were cinder block structures, flat-roofed. So, I grew up in this unusual environment. There was a lot of music around and a lot of art and people talked easily. We could walk in and out of people’s kitchens, as kids. I loved growing up there. I could go into the Seligman’s house and sit down and they would talk to us like adults, not like children. It was nice. That’s a background which actually has fed me a bit because it was polydisciplinary. There were a lot of different kinds of people doing different things, including composers. There was one who was an actress and singer [Tamara Drasin], and another who was a composer.

So those things were slumming around in my head with more than one media, in my young life. As a child, exploring the weeds behind the house and in the woods and seeing turtles and listening to birds and crawling over things and looking at the sky was for me really all one thing. And that was important stuff for me. Maybe this is why the integration of the arts was so obvious to me later. Somehow the early, early stuff was very real and a lot of what I was getting from the culture was not as real, especially TV. Whatever I saw on TV was complete anathema; it was insane to me.

My father and mother were very generous to us as kids — the toys that they got my brother and I were wonderful. One of them was “make your own motor”; you had a spool of wire and a couple bars of metal and a piece of wood and you made your own motor. Another was the Erector Set, I loved the Erector Set. You know, this is kind of Erector Set technology [laughs]. Erector Sets 2[2. A children’s toy popular in North America during the first half of the 20th century. Metal parts, small motors and moving parts could be assembled in myriad ways to create model structures.] were great because you had pulleys and gears. It had a gearbox that I loved. And my father used tools, saws and pliers; he had a lathe. I would say that even electrically I didn’t have any education about those things, but somehow it came to me easily. I don’t know why that is, but when I needed to do electrical work for my projects later, I was fortunate that my parents had provided these childhood opportunities.

From High School Jazz Musician to Chicago Painter

I was a musician as a child and very thoroughly introduced to music — between classical music and classical guitar music and my mother and father being involved with jazz and folk music and classical music — so there was a lot of exposure. I was quite proficient at classical guitar. I played concerts and then became a jazz musician and played bass. It was mostly New Orleans stuff and we were a New Orleans and blues group. It was actually a subsidiary of the Tiger Town Five at Princeton and we took the jobs they couldn’t take when their band was already booked. We played some slightly bop-oriented pieces, but mostly it was New Orleans music and Kansas City music and Chicago music. We went to Europe and we were the ship’s band on a Holland American line the day after I graduated high school. I got on a ship with my bass and these four other guys for the whole summer. That was jazz, that the Europeans really loved, and it was an amazing summer. Culturally, returning to the United States was a bit shocking, particularly television. The $64,000 Question 3[3. An American TV game show that ran from 1955 to 1958.], that’s what I saw when I got back from Europe — “What the hell is this?!”

When I first went to the Art Institute of Chicago, I built an Indian sitar, my own design, because I fell in love with Indian music, in 1955. I was playing some Indian music and built this sitar with two gourds and put together this large thing. I sat on the floor and was playing Indian music and some of my own music on it. So this music was here, but I ever didn’t feel that I wanted to be a virtuoso of an instrument, because it was somebody else’s music. Somehow, I felt I had my own music to make, so I’d have to become a composer or something else. And after going to Europe with a jazz band and seeing the museums, I decided the visual world was for me.

I started to paint in New York when I came back from that trip to Europe (I was already drawing when I was a child). I went to the University of Michigan first, and was painting in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It was in Ann Arbor, though, that I got a job with the University of Michigan Theater Department, just to make money. I had to pay part of my tuition and that got me involved with light and lights in the theatre. And it was interesting to me — the whole thing in the theatre was interesting, in performance. So, there I was, embarking on a career in visual art — I couldn’t call it a career at that point; I was just wanting to see where I could go with this. The Once Group was just starting — I think Robert Ashley was there. I’m not positive of this, but I heard and was aware of some early New Media ideas floating around. So that was just a little bit of an awareness I gained about multimedia art. It excited me, too. Because I was thinking, you know, “What’s happening here?” I didn’t like living in Ann Arbor. I didn’t like being in a college town. I really wanted to be in the city, so I went to Chicago to the Art Institute and got involved with painting.

San Francisco and the Integration of Media

After living two years in Chicago, I couldn’t stick with that either. I was really drawn to some other environment, and there were things that led me to San Francisco in 1960. The places I first lived in San Francisco included one place in the north, North Point Street, near Fisherman’s Wharf. And the next place was on Twin Peaks. And then the third place was on the Embarcadero. I finally found a loft on the Embarcadero. It was a 10,000-square-foot loft that nobody wanted — nobody! — for $200 a month. I rented most of it, so it didn’t cost me anything.

One of the first people I met was a mutual friend of Ramón Sender and Morton Subotnick. The Landors were an art-conscious family, Jo Landor was a painter as well as the artistic director of Anna Halprin’s dance company. She was also the wife of Walter Landor, a pioneering industrial designer — they held a lot of parties. My father knew them; he as living in San Francisco. So that finally, I think it was Jo Landor who said, “You would really, I think, enjoy meeting Ramón, because he’s a lively guy. I just think you’d like him. You can talk with him about sound and music, as well as visual things. He’s mostly interested in music.” So, I looked up Ramón. I just phoned him up and he said, “Yeah, come on over.” So I went over and we met and we had a lovely conversation. And he said, “You have to meet Mort.” The next step was going over to Mort’s house and in about a week we all knew each other very well.

They were about to embark on some mixed media, New Media — exploring whatever we could do, whatever we were excited about or thought about — at San Francisco State University. The Sonics series was the first event bringing together of some of their ideas. I participated in two or three of the early sessions. I was setting up my painting stuff in the loft in the Embarcadero and thinking, “What can I do with Ramón and Mort?” I just kind of had a spirit of “anything that has meaning with sound is real.” I first started with some slide projector they took apart and put a rheostat on the lamp and fixed the lens so I could manipulate it in live performance. I started making lenses like this [shows an example], which could make a very hot image a long distance away. It’s a 12-inch lens. I just found these lenses on Market Street in San Francisco; there was an Army and Navy Surplus. So, I started making lenses and using things like prisms to move light around, because the whole thing for me was “light in motion was music.” And music and visual for me was not a separate kind of thing.

What I think was in the air in San Francisco for me was an opening, because I was basically a New Yorker, in a way. Most of the people in Roosevelt were New York-oriented. But in San Francisco the sky was big and the land was in hills, and people were not thinking about happenings, nobody talked about happenings so much. But there was an instinct, I guess, of finding a way, finding a way that works for me, and for a feeling that’s not necessarily named. And that’s why I was excited about being with Ramón and Mort, because it wasn’t named. We did an opera — a washing machine opera, where they put stones in a washing machine. And I projected on the garden outside the windows with a film projector that was only going at eight frames a second. I put some old film in it and this was about light and sound together.

The Æsthetics of Abstraction and Narrative

I wasn’t interested in telling a story narratively. We’ve become such a narrative-oriented culture that it’s hard to explain to young people that for me, abstract doesn’t mean abstract. It means that the light on the edge of that branch is absolutely wonderful in the way it’s relating to the sky. It’s not abstract, that wonderful light, vision, feeling, you know, and it doesn’t always have to be “so and so turning the door to open the house to go up the stairs to meet their girlfriend” — it’s “light and visual things can be like music.”

And this is not to put down stories, because I love stories. My wife is a storyteller, and essentially, I end up making up my own stories. But light is like a palette where there are colours and there are light and dark. First of all, I should say there is light and dark, there is small and big, there’s enormous and there’s tiny. There is sizzling or brilliant, there’s soft or slimy, dark or brooding. All of these things are available, and I realized they were very available with projectors of different sorts — I never used only one kind. As a matter of fact, through my whole life, it’s probably been my undoing, because I never became a video artist, I never became a filmmaker; I never became a light show artist, either. It was composing with whatever I could use to make a composition. And luckily, Ramón and Mort were making compositions of sound that interested me (Fig. 3), so I didn’t have to make my own (which I didn’t mind doing in a hap). But for me, putting together visual dynamics, in other words, creating a visual language of enormous and tiny and brilliant and slimy and dark and fuzzy and all these things, it was a wonderful way to be a visual artist, alongside painting. For me, there was and never has been a big separation between different visual media.

It’s not referential according to art paradigms, cultural or stylistic paradigms. To me, it’s more of an open palette of inspiration. And it’s not even about expressing the self. It’s not as abstract and flamboyant and big as I got with light projection. Sometimes these were 50 feet across, because you could do that and you couldn’t find a piece of canvas that big. So, with overhead projectors and film projectors and modified slide projectors, I could fill 50 feet. Right? But it was not Jackson Pollack. It wasn’t me expressing myself. It was more about putting together a visual language, as if I were a vehicle for that, perhaps more akin to other periods of painting, and also akin to some of the other explorations in film making, like Viking Eggling and Anton Pevzner and Naum Gabo and those people in the ’30s.

It’s about capturing things that you actually notice, that you experience — some of that but not always, because I could do it blind in a room without referential stuff. For me, it was a well of resources of visual dynamics, which are the same things they teach you in art school. It’s all texture and colour and big and small and shapes, and all of that, put together with sensitivity and maybe a very focused theme. When I was working with Mort, we did a piece called Mandolin that was very focused because it began with a viola player and went to a piano and sort of went outward and through, like a kind of poetry. It was for me a very broad vision of poetry — vision poetry — so I liked that piece. That was one of the catalysts, where I could feel like I could compose, and I actually wrote down things about it, actually making a visual score of it, finally. I didn’t even save it. I just wanted to write it down to remember, and that was my combination that worked well. I did not use film; I just used overhead and slide, mostly overhead projection with that piece. In fact, the first time we did that, the guy who lent the piano for the San Francisco Tape Music Center concert said: “What are you doing to my piano?!” He had lent us a Steinway, a huge Steinway. I was projecting liquids all over it and he thought — from what he was seeing — that we were destroying his piano.

The other piece we did was Desert Ambulance 4[4. 1964. For accordion, tape and hand-painted 16 mm film.] of Ramón’s, which for me was very interesting, because I did make some film for that. And these were techniques I learned later that Stan Brakhage was very much known for. For me, it was slightly different than [Brakhage’s work], because I was composing feelings of my own vision, from film, by painting it, by making holes in it, by slowing it down to 8 frames a second, speeding it up during the piece. I had a rheostat for the film projector. That was nice. It was an old Bell and Howell that you could dial up the speed. You can’t find them now. And so I used that projector.

The other thing that was modulateable was the light — my thousand-watt lamps were all modulateable with big, heavy Variacs. 5[5. Variable transformers.] And that was so smooth I could cross-fade two images in five minutes. Very slowly, and I like to do that sometimes. Ramón’s piece was unique for me in that I could work slow and develop, over about 17 or 18 minutes, a visual thing that was like a painting-in-time that changed. It was one painting-in-time; it was five paintings-in-time that were one unit.

And so those two pieces were kind of a beginning which led to a repertoire of forms, and some materials that I still use. As for new technologies, sometimes I stay away from the going thing. And then, usually, I get involved but I don’t grab it up right away. It’s part of my personality, I go slow with the new. It isn’t the particular medium that fascinates me. I used to talk with Nam June Paik, who talked about global media a lot, and McLuhan. I also like what McLuhan said, but there’s some separation in my thinking that the medium, the tools, “are the message” only so far as they are applied. He wasn’t saying that wasn’t true, but it was pushed in that direction that “it’s the media that’s all happening now.” I’m not so sure. There’s fresco painting and then there’s Masaccio fresco. So, for me, that the whole world was filled with amazing, connected media tools was wonderful, but it wasn’t the identification with the æsthetic. For me, an optical event could be moving or not. If it was moving, great, but if not, then not.

Collaborating With Pauline Oliveros

Working with Pauline was great. We met at the San Francisco Tape Music Center; I think we met on Jones Street. The first Tape Music Center was on Jones Street where we had an apartment, ground floor. I was painting on plastic that was all around the edge; I was behind the plastic and painting on it. There was a lot of musique concrète going on. I think that’s when I met Pauline. She wasn’t doing that particular night or evening.

But soon, over Divisadero Street, we started working together. Pauline was actually in the Sonics programme once (I’m not sure what performance). She was using oscillators then. We were rubbing elbows in ’62 and then in ’63 we certainly started together playing with things. She finally did some very interesting pieces using pure optics. There was George Washington Slept Here 6[6. 1965. For amplified violin, film projection and 2-channel tape.] and George Washington Slept Here Too. 7[7. 1965. For four performers, piano, toys and slides.]

I used a prism; I still have the very prism I used. It was broken and that made a great shape. And these [indicates] were the directions of the light to put through it. I put it next to the piano and it rotated. When I aimed a beam of light through this — I would cut out an image out of a piece of metal and project through it, just using a long lens — a spectral image would come out of the black-and-white image, as they scanned slowly 360 degrees around the whole auditorium, from just a little set up on the piano.

I had one prism that was cracked and one that wasn’t. Having both was an interesting aspect of my setup, I knew that the cracked prism was going to bend the light. I didn’t know if it was going to make more than one image when I picked it up on Mission Street or Market Street. When I went home, I just used a regular projector, turning [the prism] in front of the light. I noticed that I could easily get a black-and-white image which goes through that way [indicates a place on the prism], and when it turned, that would combine with a spectral image, which was coming from this direction plus that direction [indicates the place], if it was split right there. As it turned, one manifestation of the image would come out. And the crack took the rectangular shape from the image, if I was using a rectangle. That I liked, because I didn’t want a rectangle moving around. I wanted my own shape moving around. So that actually helped. The other one worked normally.

Usually, I used images that weren’t square anyway. Like the slides I used at the Electric Circus. This plus sign here [displays a slide], that could travel around the auditorium and be a spectrum and a black-and-white plus sign that would go in and out of itself. Stuff like that. There was another slide with dots — I think I used these dots in a light piece for David Tudor. That was placed on a turntable. I made a couple of these turntables and they moved real slowly. This was a one-revolution-per-minute motor, and it moves this back and forth with a cam. I just thought: “Hey, how do you do this?” I got my pliers. Usually, I just made whatever I needed. So, this turns around because it’s driven by a cam that goes back and forth; this prism goes on here. The prism could just go back, make almost 360 degrees and go back the other way. It’s just very slow, a very meditative kind of thing. Sometimes my work was very meditative, sometimes it was very robust. I had a repertoire of different kinds of equipment and stuff to do those different things. To make large projections of small slides, the optics of the thing, again, came kind of naturally to me. I could envision this could become a twenty-foot wall. It was experimentation.

That was a very nice thing that led to another light piece for David Tudor. Basically, Pauline put together the Tudor Fest. David came to San Francisco for about four days, three days of concerts. That’s when Pauline and I worked together again; I did one of those concerts. And then a major working together was for Ramón’s Desert Ambulance, because Pauline was the original accordion player for Desert Ambulance. 8[8. Ramón Sender, Morton Subotnick and Pauline Oliveros founded the San Francisco Tape Music Center in 1962, with the help of engineer Michael Callahan. They were joined soon thereafter by Tony Martin and jazz drummer William Maginnis.] I made a film to put on Pauline. It was an abstraction plus film showing people walking and marching, and hands playing piano sideways. I used the negative to project on the white keys of her accordion and the white lab coat she was wearing (Video 1; Fig. 5). After the whole first five minutes of the piece, I put the cutout of Pauline in behind the focal plane of the projector upside down, so it would turn right side up when projected. The shape of the projection was just on the body of Pauline. I’ve never been able to make it that tight since. There’s always bleeding. In a new projector, I can’t put in a piece of metal. It’s going to ruin the whole thing.

New Visual Control Technologies Parallel to the Buchla

The suitcases that contain my light boxes were kind of the answer to Don Buchla’s sound synthesizers — a visual control apparatus. Carl Countryman designed it at Mills College. We talked about it, I think, at Divisadero Street, but I’m not absolutely certain we did any real planning on it until we got to Mills. Countryman came over and we discussed the making of a unit that could control on and off switches for projection equipment that could be up to 1000 watts. He came up with a system that routed the signal through a filter system, here [shows the place] and these were high- and low-band-pass filters that you could use to narrow a band and take output, with banana plugs, here, and control the input and the output, the gain on any 1000 watts (input). So this was 20,000 watts capability, just from a suitcase. The sound coming through here could be filtered in any way — or not filtered — and put into the inputs of these SER circuits; there were preamps in here. It’s beautifully made. The back of this board is lovely. He’s got all the preamps sticking out. The other part of it that I really wanted, and we talked about it a lot, was a counter so that things could go off and on according to a “clock” of sorts, a logic circuit where you could put in a pattern of up to 20 nodes of any time. It could be a rhythm, or other kinds of events that unfolded automatically for, let’s say, 15 minutes.

Countryman developed his system at the exact same time that Don Buchla was building his sequencers and other gear for the Tape Music Center. Countryman and Buchla were the same kind of guy, different personalities with the same electronics savvy. When I was invited to join the Intermedia Center at NYC, in 1967, in the Spring, Mort Subotnick had already commissioned Buchla’s equipment. I ordered another one of Countryman’s units because I left the first one at Mills College. The new one was basically the same thing put into one unit, where I had some relays so I could turn film projectors on and off without splitting all the circuits.

I was once on an airplane flight and a member of the flight crew said: “What is that? What is in that briefcase?” They were worried that it could catch on fire or explode. They had somebody from the cabin come back and look at it. I pointed out that there’s no power supply in this thing. And he said: “Oh, ok.”

Transitional Times for the San Francisco Tape Music Center

Mort moved east in 1966 and I followed in 1967; this happened during a time of change for the Tape Music Center. The Center was confronted by an issue of whether to continue as it was or get some big funding. And the Rockefeller Foundation was wonderful to us. Boyd Compton 9[9. A Rockefeller staff member at the time.] was a wonderful guy who came to the West Coast, saw what we were doing and said, “This is wonderful and we have to do something with it.” So he went back to the Rockefeller Foundation and they said, “You can have a big grant. You can’t be an isolated institution. You’ll have to join up with somebody.” The logical people were Mills College, because they had the most advanced musical thinking at the time. Darius Milhaud was there. It seemed like they might be interested — well, they were. Becoming part of an academic institution meant a fundamental change and we didn’t really want that. Each of us had separate feelings about it.

I was really like a bird in a wind. The wind was blowing real strong and you could go with it easily. But you had to really flap. You had to really work hard to go in your own direction, because the social wind was so strong. It was a very complex time of assassinations of our most wonderful people and artists who were making new combinations of things. And a lot of us were involved in this environment because we were really conscious of a changing society. So we weren’t isolated and I didn’t want to be an isolated studio artist all the time.

We all knew that it was going to be a new kind of thing. Ramón had gone to live a commune kind of life. And Morton was invited to go to the NYU School of the Arts. Also enticing him were a few commercial things. In 1965, Mort decided to go become part of what soon became the NYU Intermedia programme and then I was naturally going to stay in the Bay Area — there wasn’t any huge attraction for me to New York City at that point. The thing that became nice was that they offered, or we decided, that there could be a more easy transition if Pauline and I both stayed with the Tape Music Center. So Pauline was taken on as the Sound Director of the Tape Music Center at Mills College and I was the Visual Director of the Tape Music Center at Mills College, beginning in September 1966, I believe. We were there three days a week, more or less, Pauline and I, sometimes on different days. And we did interesting things. Sometimes I had students. Strangely enough, I did a visual score for Monteverdi’s Poppea, a visual environment — while the musicians were singing, these visual projections moved all around in the background and around the edges of it. It was one of my favourite pieces of music, very exhilarating. I was really into it in the projections. But the transition to Mills wasn’t easy for me.

I did an abstract visual environment for that beautiful auditorium at Mills College. We put it together so that it cost, I think, just a few thousand for the year. Also, I was a carpenter some of the time. And I had been doing the light shows for Bill Graham at the Fillmore West with the Jefferson Airplane and Grateful Dead and Muddy Waters. I really loved the blues programme, working with Paul Butterfield, the blues band. It was a weekend gig; on the weekdays I [was with my] new wife and child (Ben was born in ’65). The transition to Mills would have meant travelling to Oakland. At that point I was living in San Raphael. To get to Oakland I’d have to go over the Richmond Bridge. I was out of the Embarcadero loft and I was still painting. I knew it was transitional.

The Move to New York and NYU

I said to my wife that I really didn’t think I could stick with the Bay Area. One day I was up on Russian Hill and I could see everything — the whole city. I thought, “Oh, I have to go back to New York!” I really did feel the pull of New York, partially because the visual world of New York was much broader.

When Mort phoned up one day and I told him I was thinking about not staying at The Tape Music Center, he said that I could come and introduce myself to the people at the NYU School of the Arts Intermedia programme. They made an invitation for me to go, and so I went there with my projectors and did a show for the directors at the chairman’s house there. Everybody flipped out and said, “Hey, this should be part of our thing.” So, I got it. Len Lye 10[10. Kinetic artist and experimental film maker originally from New Zealand, naturalized American since 1950.] was already involved with them, as well.

I decided that indeed it would be good to move to New York. So, in the spring of ’67, I took everything I could pack up, including my young child, and we put everything in my Volkswagen bus bought from money from working for Bill Graham. We put everything in the bus and sent a bunch of stuff by United Van lines and ended up on Bleecker Street. So there we were, not knowing where to live or anything. I brought myself, my family, equipment, my paintings, and set up a new life.

We first lived with my wife’s parents in Stuyvesant Town 11[11. A complex in downtown east side Manhattan.] because she was pregnant again. We lived there for about a month and then we almost went into a place on Tompkins Square. I met an old friend, Leon Golub, and Peter Passuntino and Bob Bornstein (all three were painters); we rented a five-story building from NYU on West Broadway on a block that later became LaGuardia Place. We got a really good price for renting it (and later bought it from the university). The third floor became my studio and my home with my new family.

I started to work in the Bleecker Street studio 12[12. See Bob Gluck’s “Interview with Charlemagne Palestine, Composer and Visual Artist” in eContact! 20.3 — Shortwave Radio, CD Players, the Inner Ear and Waltzing Goldfish: Medium-specific practices in sound for some insight into the rich tapestry of artists Morton Subotnick’s studio brought together and supported.] where the NYU Intermedia programme was, on the second floor above the Bleecker Street Cinema. 13[13. Founded in an NYU-owned building in 1960 and in operation through 1990, the Bleecker Street Cinema in Greenwich Village was one of three prominent and influential New York City art-house cinemas.] I had a studio that I shared with Len Lye and another little part of a studio that was all my own. I was in another part next to Mort, behind him in another room on the second floor. I could use the bigger space with Len Lye when it was available. And he was using it less and less. Len finally left in ’67. He was storing stuff there but wasn’t there very much. Len and I didn’t collaborate. We were just in the same studio and shared the gallery representation because Howard Wise Gallery was showing Len Lye’s work, the big magnet pieces that went from one side to the other. 14[14. I’ve since become friendly with Len Lye’s son Bix, because he lives ten blocks south of here in Williamsburg and we’ve become friendly over the past many years. I’ve been in this place right here in Williamsburg for 25 years. So this has become a whole other world.]

At any rate, the move to New York was a rigorous and large change for me. And again, I had to put together an income. We were called master artists-in-residence. It wasn’t a regular class schedule; it was studio-oriented and paid something like five or six thousand dollars a year. It wasn’t going to be enough, but Mort put together some income for us. I worked at the Electric Circus.

My situation as artist-in-residence was not the same as Mort’s, who had a cadre of composer assistants, but I had my entourage as well: Bill Sward and another guy. Also, Serge Tcherepnin (whose nephew who lives near me now and who worked largely with Mort) built a little piece of equipment for me, a proximity detector, so I could have viewer participation from proximity devices to turn things on and off. The technology was field effect transistor (FET). He built me a little unit I still have. So, I had my own little cadre. Also, I started to build the interactive pieces there, the pieces that became my two solo shows at the Howard Wise Gallery.

My interactive work actually dates early, to a collaboration in San Francisco in 1962 with choreographer Anna Halprin. That piece was a large-scale, room-sized, octagonal 20-feet-in-diameter interactive environment. It was there for about a month, so that the audiences who went to the museum were able to go to that space. It was a poly-sensory environment, where the viewer made choices. I always felt that was the beginning of what happened at the Howard Wise Gallery, where I made truly interactive pieces, in ’68, ’69.

Howard Wise was connected with NYU; he helped to fund some of the things that occurred through the Intermedia programme. He helped to support those interactive pieces that I was building, for instance, so the school didn’t incur the costs of the materials. David Oppenheim was the head of the School of the Arts. So, we did the best we could. We were kind of driven ourselves. Morton was very driven in doing what he was doing with the Buchla equipment and his own work, and was working with students and with other groups. And I was very intensely making new pieces for these one-person shows.

I also collaborated with choreographer Jean Erdman at the School of the Arts, a visual thing at the Whitney with her and with a new music composer who was a jazz composer from Cal Arts. So, there was some activity with the School of the Arts. We tried to set ourselves up as an attractive thing, to attract students. And sure enough, we did. But there wasn’t enough rigorous scheduling, as far as I was concerned. It was very loose… it was overly loose, actually. So I was left floating a lot of the time in the studio there, not know when I’d have a student or not. There were times they were supposed to be there, and sometimes that occurred. I had sessions with students.

The Electric Circus and Liquid Light Projection

My position at the Electric Circus came about from an invitation to come over and tell them what I was about. There wasn’t a need for a big introduction. They already knew what I was able to do with projection equipment, from the Fillmore West. Stan and Jerry went out to the Bay Area to look at the light show. I didn’t meet them there, but they met my associate Bill Sward, somehow, and he said, “Oh, like an electric circus!” — he may be the origin of that name. The visual palette for the Electric Circus came by observation of what happened on the West Coast. I spoke with Jerry Brandt and Stan Freedman 15[15. Founders and owners of the Electric Circus, an iconic event venue in the East Village that was active from 1967–1971.] right away. I think Susan Burdon was also involved in management, although maybe she wasn’t there at the very beginning. There were at least two other people. But first there was just Stan and Jerry.

And I pretty much enumerated what I’d think of doing, which pretty much lined up with what Buchla was designing — a control system for sound and projection equipment. It was an absolute natural for me to have 16 mm film projectors, maybe four overhead projectors and eight slide projectors, working to programme and film.

The projection component was substantial. It wasn’t derivative of what Andy Warhol had done previously, at the same location as the Electric Circus. It was new, based upon Mort’s conception. The idea of a “circus” was something I liked — the notion of a circus. I liked a lot of their vision, which I thought was very interesting. The original feel for me was that it was a democratic, horizontal coming-together of different kinds of people, with stimulus and vision. It interested me; I could work with that. I ended up making projection materials — with Don’s circuitry, I could combine these images in any way. I could make glass slides — 640 slides, 80 in each projector. Finally, Bill Sward and Michael Malone (who became a very well-known tattoo artist) and I, with the help of a couple other people, basically, the three of us sequenced the materials and light events with Don’s equipment at the Electric Circus.

I had developed all of the liquid projection techniques pretty much on my own in the early days of the Fillmore. 16[16. Here Martin is referring to the Fillmore West, a famous San Francisco rock music venue directed by promoter Bill Graham from 1968–1971, and not the Fillmore East, also run by Graham but located in New York City’s East Village.] That was Winter ’65, and the Trips Festival. 17[17. Organized by Ken Kesey, Stewart Brand (Ken Kesey and The Merry Pranksters), Ramón Sender and Bill Graham, the Trips Festival was held at the Bay Area’s Longshoremen’s Hall 21–23 January 1966. With its immersive and participatory multimedia experience of music, dancing, theatre and lights — not to mention free LSD — it is seen as a key turning point and framework for the then-emerging hippie counterculture movement.] I was working with liquids, but others had worked with projectors. The first time I saw it was Elias Romero doing liquid projections with jazz musicians, on Capp Street. There is a little performance place and jazz people would play and he was doing liquid projections with jazz. That’s the first time I saw liquid projection; I think that was ’63. I took it in my own direction.

Since I was a painter, I used to make acetate drawings for slides, and use dry substances like string and powders, as well as found materials, in combination with the liquids. Anyone could squish two glass plates together with liquids between them to make “amoebas”, and I was good at that because I had a lot of rhythm, but it was not my favourite technique. This was psychedelia, rock psychedelia, and that was not my major way. But it brought bread to the table and paid the rent. And also, I enjoyed working with a lot of the groups. The Byrds got me to go to the Whisky-a-Go-Go in Los Angeles — that was my more commercial enterprise. But my heart was really into a more local interactive kind of environment. And also composing with light.

Working with Jerry Brandt was all right. He’s a different kind of person than me, involved in entertainment and the entertainment world. But I liked his spirit. He’s very filled with enthusiasm, a lot of energy. He has a true love of rock and soul music. I don’t think he was as visually oriented. Maybe he was; he was aware of how exciting it was to have a multi-sensory environment, very aware of that. He went on to do things with rock bands and soul. I remember how excited he was about Aretha Franklin. She may have been at the Electric Circus; I don’t recall been. Certainly, a lot of the music at the Electric Circus was pre-recorded records. Beyond that, I didn’t know him really well… mostly in the office and around; he’s working while I’m working. Morton had more of the organizational type meetings with them. I had some. Actually, I had quite a few, but that was after pretty much everything had been put in gear.

Electric Ear Series

The early days of the Electric Circus were exciting — putting things in slide projectors, combining them, seeing what would work and what wouldn’t work was satisfying. And that became every day and humdrum and Bill and Michael were doing more than I was. I would hardly go over there, even though it was a major part of the whole operation — and it was what I was getting paid for.

For me the daily concerts, music and dancing became a routine because I had to make sure it was going to start and run and function. I had to go over there every night it was happening, at the beginning. I could walk from St. Mark’s Place across Washington Square in ten minutes: feed my child, walk across to the Electric Circus and make sure the projectors were in shape and that Bill and Michael were there. Maybe I would stay there for an hour, running things, and then I would leave. I was loading those projectors with images. I would be over there two or three times a week, at least.

Mort was thinking about doing something else that was closer to our hearts, of electronic music, new music and composed visual stuff. Mort, Thais Lathem and a few others put together the Electric Ear series. 18[18. For more on the Electric Circus and the “dark, dark nights” of the weekly Electric Ear series,” see Bob Gluck’s “Conversation with Eric Salzman, Music Theatre Composer and Producer,” published in eContact! 18.3 — Sonic DIY.] It was actually very nice. Thais was terrific. We had this ability to work with different groups and different places. Although the daily parts of my work at the Circus consumed much of my time, I was more interested in the Electric Ear. I have an original programme from the Electric Ear, from August 26, 1968. It was The Wild Bull and The Closer She Gets. 19[19. Martin created both of these pieces in collaboration with Morton Subotnick.] There’s a little blurb on me and Joel Spiegelman. And Elaine Summers, the dancer who was involved.

Then it became interesting to do some of the events with the Electric Ear. And so Morton and I had a good time putting together that programme. And the facilities were great — all we had to do was walk in. I did work with whoever was performing. The Electric Ear was good. For one of those we did a piece. I forget how we called it. I just used light bulbs, no images, no projectors, just little lights flashing on or off or making glow or making an aura of a light in a certain shape, directly using the sound as the triggering mechanism, but with control over that. I would dial thresholds and filters. I had glass rods that lit up, fibre optics that lit up, all from the sound, from the Countryman device. That was fun.

I think there were other events that would happen at the Circus. On a Saturday afternoon, they would have an event, a fashion show that was paid for by fashion people. There were a couple of fashion shows, and other kinds of events, along with the light show, dance and canned music, a lot of the time.

Changes at the Electric Circus

When they decided to make a new environment inside it, it really got kind of dirty. It was basically an L-shaped wall and the other L-shape was the projectors. I liked it, actually, it was good for projections, the end wall and the side wall. So they decided to make a big change — they brought in Ivan Chermayeff and the other guy, Geismar. They made a stretched fabric environment out of the whole inside of it, which made it more like a circus, in a way — I liked that. I thought it was a well-designed stretch fabric environment that was excellent for projection. I changed some of the projection ideas, a little bit, more of the slides interwoven with each other and tighter, and the film projectors more organic, just happening on curved fabric. It began to run as a more elegant kind of environment.

That did not increase my interest, however, it just brought it more fully to where I thought their vision was taking more precedence and I could bid it farewell. This is what I helped to make happen and now I could go away from it. So I gradually went away from it. I was just there less and less and gave more authority to Bill Sward and Mike. My work at The Electric Circus ended when it just stopped working for me. I don’t even remember how it eased off.

My wife at the time [Dinah Friedman Martin] did an interesting thing with Michael Malone. They made a children’s theatre on Sunday afternoon at the Electric Circus and it was quite inventive. Mike would make slides for children that provided participatory environmental situations. That was really healthy, another thing that came out of it, another sideline like the Electric Ear.

Other Downtown Artist Collaborations

In ’69, when I knew that I would probably be going away from the Electric Circus, I got involved in the Experiments in Art and Technology. 20[20. Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) was founded in 1967 in order to encourage collaborations between artists and engineers.] I designed the light system with engineers. That was wonderful because I could work with pure light, no projections. I love working with pure light, on a grand scale.

I also did an interesting piece in collaboration with David Tudor with Merce Cunningham’s troupe. My premise was to use elliptical reflectors and parabolic reflectors to gather information from the dancers. And focus that on informational apparatus, like photocells that could be transmitted back from the environment, to make a loop. I would collect information from the dancers and use it for their lighting. Controlling the lighting of the space by the movements of the dancers was not an easy thing to do, but it worked.

I worked with Charlotte Moorman quite a bit. We had some good things that happened. One was the South Street Seaport event when we used the Ferry Building. I did a piece on the inside of a ferryboat with a light pendulum — I’m going to be doing a new version of the piece. The light pendulum would move because the ship was moving. And it activated light events in that area, from photocells that were in a reflector that was underneath this illuminated pendulum. It was a self-generating environment from the movement of the ship.

I think there was an overall kind of mutual nurturing thing that was natural to the life that I was certainly involved with, that I liked. Talking with Jean Erdman, Merce Cunningham, David Tudor, with Morton, a lot when he was there.

After Morton went to California, I didn’t see Morton as much. I had to get a teaching job, just for money. I found a position with Kingsborough Community College in Sheepshead Bay, a neighbourhood in Brooklyn. That was a lifesaver because basically it was my income (I now had two young children), and I started a little bit of a media thing. Not a big one but I did some work with that. Some time I had to be around the general scene. So, I did what I did. I got involved with certain things but did not get enmeshed. The happening era had pretty much subsided by that time, so there wasn’t that part of the downtown scene. 21[21. “Interview with İlhan Mimaroğlu, Turkish Composer: Uptown and downtown, electronic music and ‘free jazz’, Ankara and New York” in eContact! 14.4 — TES 2011: 5th Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium (March 2013).] But there was a lot of concerts and activities and media events that were happening all over the city, in churches, in universities like Princeton. There was a programme there headed by James Seawright, he invited me down there. So, there was connectedness between some (but not all) of the artists at that time — you never knew all that was going on.

Lack of Documentation

There’s too little information about that period from ’62 to ’72. It’s a decade that was not available for video people at the time; because nobody had digital at the time; there were only 66 mm cameras and nobody was really doing documentary work in any kind of detail. You, I think, are doing an important thing by trying to fill that gap, so people have some information and exposure to it. I’m hoping that gap will be a little bit rectified because truly there is a lack of awareness of a lot of the seminal work that was done in those years. Recently David Bernstein wrote a book about the San Francisco Tape Music Center.

But this work is not better known for a number of reasons. One factor is that I was not a social runaround kind of guy. I was involved with some of the downtown scene, but I was always so busy. There was a lot that I did not observe. I was living in Soho and it happened all around us. Artists like myself were involved, first on a more isolated basis. We were just singular people in lofts. And then finally it became a very main area for a lot of people, which was very, very exciting, generative.

There’s a remarkable absence of material. It seems incredible how little was photographed or filmed at the Fillmore West or at the Tape Center or at the Electric Circus. We were so busy and so much doing our work that we didn’t spend time on documentation. In terms of the artistic environment at the time, it’s very different now than it was then. Now, people get MFAs about how to document their work. We had none of this. By the seat of our pants we were involved in creating the best that we can, our vision. It was a different way of working. I’m not saying a lot of that doesn’t happen now. We just were not doing much documentation then. And we paid the price, being less exposed, less known.

Just recently, John Hanhardt of the Whitney Museum included my work at a lecture he gave at the Fales Library 22[22. The Fales Library & Special Collections Center at NYU’s Elmer Holmes Bobst Library.] as one of the downtown artists. They have a downtown artists collection that is growing. Richard Forman’s material is there. I decided to give them my archives of that period. So, the Fales Library has a lot of my papers. My material is just getting looked at; it takes a year for that. It includes video and some drawings.

March 2008, April 2022

Postlude (May 2022)

An essential understanding of Martin’s work hinges upon his tandem path of the disciplines of drawing and painting combined with his light and media work. Beginning with his student days at the Chicago Institute of Art, Martin embarked on a rigorous quest of exploration, letting these different fields fuel and cross-fertilize 50 years of endeavour. He exhibited in national venues and internationally, in such countries as France, Japan, Switzerland and Korea. Some exhibitions showcased his paintings, others the interactive works, still others employed a blend, such as his computer-generated Vector Image show at P.S. 1 (now part of MOMA), which included related drawings. A few years prior to this interview, and with increasing intensity after, Martin would perform, or have works shown, at such institutions as the Whitney Museum (2015), Walker Art Center (2015–18), Pulse Contemporary Art Fair (2016), Hillstrom Museum of Art (2018), Fri Art Kunsthalle (2019) and others. In 2019, in celebration of five decades of work, Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI) and the Emily Harvey Foundation mounted a special exhibition of the viewer-activated works Martin made for the Howard Wise Gallery exhibitions of 1968 and 1969, accompanied by ephemera from 1961 to 2015, augmented by a talk and an interview given by the artist. Meanwhile, painting in his Brooklyn and Treadwell studios would remain a constant to the end. Poignantly, Martin’s death on 24 March 2021 also ended a remarkable family legacy, as each of the other three members of his immediate family were artists: Martin’s mother Thelma Durkin (painter and photographer), his father David Stone Martin (illustrator and graphic designer, best known for jazz album cover work) and his brother Stefan (painter and wood engraver). These four had individually distinguished themselves in diverse professional realms, and Tony, the second son and the most fiercely inventive, was the last of them.

Social top